I spend an awful lot of my day in Unix terminals running shell commands. For some reason, the variance in efficiency between different people when using the shell is huge: I know people who can run rings around me, and I’ve come across more than one paid professional who doesn’t use the “up” key to retrieve the previous command.

I chose that last example very deliberately: most of the commands most of us

run in the shell are highly repetitive. I typically run around 50-100 unique

(i.e. syntactically distinct) shell commands per working day1 — but

I’ll often run a tiny subset of those commands (e.g. cargo test) hundreds of

time in a single day.

Since many command-line tools have hard-to-remember options, we can save huge chunks of time – not to mention make fewer errors – if we can search our shell history to find a previous incantation of a command we want to run. In this post I’m going to show how, with little effort, searching shell history can look like this:

Searching shell history

Larger Unix shells such as Bash have long allowed users to search through their

shell history by pressing Ctrl-r and entering a substring. If I (in order)

executed the commands cat /etc/motd then cat /etc/rc.conf, then Ctrl-r

followed by “cat” will first match cat /etc/rc.conf; pressing Ctrl-r again

will cycle backwards for the next match which is cat /etc/motd. I almost

never used this feature, because substring matching is too crude.

For example, I may know the command I want is cat, the leaf

name I’m looking for is motd but I don’t remember the directory: substring

matching can’t help me find what I’m looking for. Instead, I regularly used

grep (with wildcards) to search through my shell’s history file instead.

For me, the game changer was pairing Ctrl-r with

fzf, which brought two changes. First,

matching is “fuzzy”, so I can type “c mo” and cat /etc/motd will be

matched. Second, multiple matches are shown at once. Typing “cat” will show

me several cat commands, allowing me to quickly select the right

incantation (which may not have been the most recent).

It’s difficult for me to overstate how powerful a feature this is. Few things

in life make me as happy as pressing ctrl-R then typing “l1” and having a 100

character command-line execution that runs a complicated debugging tool, with

multiple environment variables set, whose output gets put in /tmp/l1 appear

in my terminal.

Using Ctrl-r and fzf roughly doubled my efficiency in the shell

overnight. Interestingly, it had an even greater long term effect: I became a

more ambitious user of shell commands because I knew I could outsource my

memory to fzf. For example, since it’s now very easy to recall past commands, I

no longer set global environment variables, which had previously caused me

grief when I forgot about them2. Now I set environment variables on a

per-command basis, knowing that I can recall them with Ctrl-r and fzf.

For many years my favoured shell was zsh. When I later moved from zsh to fish,

Ctrl-r and fzf was the first thing I configured; and when I moved back to zsh3, and redid my configuration from scratch, Ctrl-r and fzf was again the first

thing I got working (shortly followed by

autosuggestions). If you

take nothing else from this

post than “Ctrl-r and fzf are a significant productivity boon for Unix

users”, then I will have done something useful.

No tool, of course, is perfect. A couple of months back I somehow stumbled across skim, an fzf-alike that out-of-the-box happens to suit me just a little bit better than fzf. The differences are mostly minor, and you won’t go far wrong with either tool. That said, I find that skim’s matching more often finds the commands I want quickly, I prefer skim’s UI, and I find it easier to install skim on random boxes — small advantages, perhaps, but enough for switching to be worth it for me.

Doing even better

Finding Skim encouraged me to quickly look around to see what else in this sphere might improve my productivity. I quickly came across Atuin, which is a much more sophisticated shell history recording mechanism: the video on its front page showed a much nicer matching UI than I had previously considered possible.

However, I quickly realised Atuin wasn’t for me or, at least, wasn’t easily for

me. These days I regularly ssh into many different servers: over time I’ve

streamlined my shell configuration to a single .zshrc file that I can scp

over to a new machine and which instantly makes me productive. Atuin – and

this isn’t a criticism, because it’s a more powerful tool – is more difficult

to install4 and setup5 (I’m also not sure the ‘fuzzy’

aspects of Atuin quite match the heights of fzf/skim). That said, some readers may find

it a useful tool to investigate.

However, what I immediately realised from the Atuin video is that I would like my fuzzy matcher to show me more useful information about the commands it’s matching.

In particular, fzf and skim both default to showing me a (to me!) meaningless

integer before my matched command: this had always slightly bothered me, but

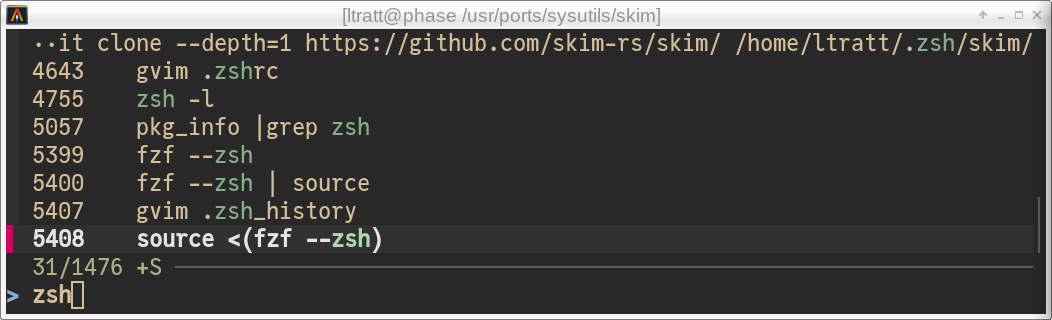

I’d never thought to work out what it meant. For example, if I use

zsh + fzf + Ctrl-r I see:

What does 5408 mean and why is it taking up valuable screen space? Skim

tries to be a bit nicer: it will show 5408 today'21:266, but that

takes up even more screen space!

Adapting zsh and fzf/skim

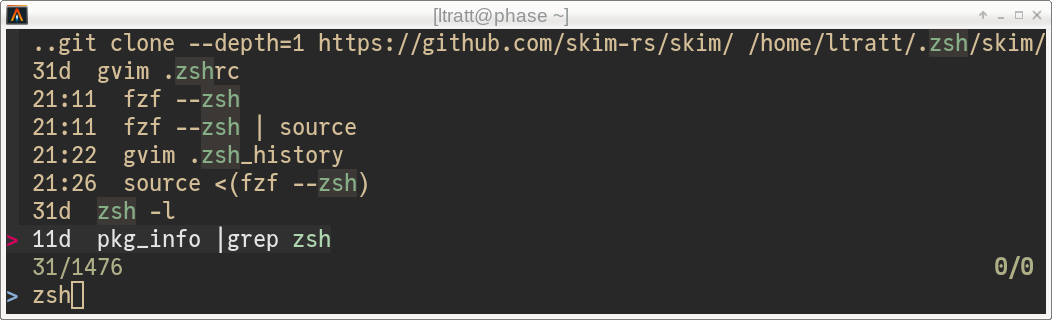

Fortunately, it turns out that improving the Ctrl-r and the fzf/skim UI is

easy. Instead of wasting space on a meaningless-to-me integer, what I

now see is the following (where 11d means “11 days in the past” and so on):

I’m going to show how I adapted zsh and skim to do this. My guess is that it

will take very little ingenuity to adapt this to other shells (and adapting

this to fzf mostly involves swapping the sk command for fzf).

The first thing I needed to do is make zsh record when commands

were executed. I added this to my ~/.zshrc:

setopt EXTENDED_HISTORY setopt inc_append_history_time

The EXTENDED_HISTORY changes the format of .zsh_history to record when (in

seconds from the Unix epoch) a command was executed and (with

inc_append_history_time) how long it ran for. The good news is that these

options migrate “traditionally formatted” history files naturally: any

non-extended-history commands will be given the current date so that

all of .zsh_history is in the same format.

I then needed to understand how zsh’s history ended up being interrogated and

displayed when I pressed Ctrl-r. fzf and skim share almost exactly the same

code here: I’ll use skim’s zsh key

bindings

as my example. In essence, both tools define a function history-widget

which they then bind to Ctrl-r:

history-widget() { ... } zle -N history-widget bindkey '^R' history-widget

One can override the version fzf and skim provide by putting the code above

into your ~/.zshrc after the point you import their normal key bindings.

Let’s look at skim’s history-widget:

skim-history-widget() { local selected num setopt localoptions noglobsubst noposixbuiltins pipefail no_aliases 2> /dev/null local awk_filter='{ cmd=$0; sub(/^\s*[0-9]+\**\s+/, "", cmd); if (!seen[cmd]++) print $0 }' # filter out duplicates local n=2 fc_opts='' if [[ -o extended_history ]]; then local today=$(date +%Y-%m-%d) # For today's commands, replace date ($2) with "today", otherwise remove time ($3). # And filter out duplicates. awk_filter='{ if ($2 == "'$today'") sub($2 " ", "today'\''") else sub($3, "") line=$0; $1=""; $2=""; $3="" if (!seen[$0]++) print line }' fc_opts='-i' n=3 fi selected=( $(fc -rl $fc_opts 1 | awk "$awk_filter" | SKIM_DEFAULT_OPTIONS="--height ${SKIM_TMUX_HEIGHT:-40%} $SKIM_DEFAULT_OPTIONS -n$n..,.. --bind=ctrl-r:toggle-sort $SKIM_CTRL_R_OPTS --query=${(qqq)LBUFFER} --no-multi" $(__skimcmd)) ) ...

The first thing to note is that – thanks to EXTENDED_HISTORY – in

my context the -o extended_history check always returns true, so the body of the if is

always executed.

We can then skip ahead: fc -rli 1 gets zsh to output its history in a more

easily digestible form than going through .zsh_history directly:

$ fc -rli 1 4 2025-02-07 15:05 pizauth status 3 2025-02-07 15:03 cargo run --release server 2 2025-02-07 15:03 email quick 1 2025-02-07 14:59 rsync_cmd bencher16 ./build.sh cargo test nested_tracing

We can also now see what the magical integers from earlier are: they’re the row

numbers from fc, where 1 is the oldest command in my ~/.zsh_history! These

are, in some situations, used as identifiers because one can ask zsh to “return

me command 5408”.

The awk code streams over this output, replacing today’s date with the literal

string today, removes the hours/minutes output from previous days, and

removes duplicates.

Although it’s easily missed, in the final line of the code snippet is

-n$n..,.. which tells skim which whitespace-separated columns to fuzzy

match and print out.

At this point we now need to decide how to adapt things to our purposes.

The first thing we need to do with fc’s output is convert the time to seconds

since the Unix epoch. We can get fc to do that for us with -t '%s'. Instead

of outputting 2025-03-21 22:10 we now get 1742595052. Notice that two

fields have now become one! Because fc adds leading space to the row

numbers, we’ll strip that off by piping fc’s output through sed -E "s/^ *//"7.

I then needed to decide how to format “how far in the past was the command

run”. After a few tries, I decided that a good approach is to give absolute

hour:minute times for commands in the last 20 hours, and 1d, 2d (etc.)

for commands 1 or more days in the past. Why 20 hours? Well, it turns out that

if I start work at 08:00, press Ctrl-r and see an entry at 08:01 I won’t

realise that was yesterday’s 08:01 (today’s 08:01 is only 60 seconds in the

future!). 20 hours solves this ambiguity: it means that, at 08:00,

yesterday afternoon’s commands show as 16:33 but yesterday

morning’s commands as 1d.

We now need to switch to awk. I will admit that I initially balked at the use

of awk, a language I have never used before. I quickly explored alternatives

before realising why the code uses awk: every Unix machine has awk installed.

For those unfamiliar with awk, the program that we’re writing iterates over

each line in the input, splits that line up by whitespace, and puts the split

fields into the variables $1, $2 (etc.). We’ll keep the duplicate detection

from the awk code above, but change most of the rest.

The first thing we need to do in awk is to convert the Unix epoch time for a

command (in field/variable $2) to an integer, and calculate how many seconds

it is in the past using systime (which returns the current time relative to

the Unix epoch):

ts = int($2) delta = systime() - ts

We can then convert delta seconds to days by dividing by 86,400 (24h * 60m *

60s == 86,400s). It’s then a simple series of if/else to format this nicely

bearing in mind that:

- 20h == 72,000s

- string concatenation and int-to-string conversion in awk is implicit

The conversion code looks as follows:

delta_days = int(delta / 86400) if (delta_days < 1 && delta < 72000) { $2=strftime("%H:%M", ts) } else if (delta_days == 0) { $2="1d" } else { $2=delta_days "d" }

One could choose to divvy things up further, perhaps showing commands older than a week with “1w” and so on: I haven’t found that worth worrying about yet.

There is, however, one minor fly in the ointment: clock skew. This could cause

commands to appear to be executing in the future. I’ve not seen seen this

happen in practice yet, but bitter experience with computers and clocks tells

me it will at some point. I’ve defensively catered for the inevitable confusion

that will cause me by using a + prefix for such cases:

delta_days = int(delta / 86400) if (delta < 0) { $2="+" (-delta_days) "d" } else ...

Notice that I had to put (-delta_days) in brackets as otherwise – for reasons I’m

too lazy to investigate – awk doesn’t concatenate the integer and

string in the way I want.

Since we have one fewer field than before we can slightly simplify our output:

line=$0; $1=""; $2="" if (!seen[$0]++) print line

That’s the awk code done. We then need to make one change to the selected=...

line changing -n$n..,.. to --with-nth $n... This tells fzf and skim to

suppress the output of the row number and not to make it part

of the fuzzy matching either.

Putting all that together, the updated chunk of the history-widget now

looks as follows (you can find the whole code chunk

here):

local n=1 fc_opts='' if [[ -o extended_history ]]; then awk_filter=' { ts = int($2) delta = systime() - ts delta_days = int(delta / 86400) if (delta < 0) { $2="+" (-delta_days) "d" } else if (delta_days < 1 && delta < 72000) { $2=strftime("%H:%M", ts) } else if (delta_days == 0) { $2="1d" } else { $2=delta_days "d" } line=$0; $1=""; $2="" if (!seen[$0]++) print line }' fc_opts='-i' n=2 fi selected=( $(fc -rl $fc_opts -t '%s' 1 | sed -E "s/^ *//" | awk "$awk_filter" | SKIM_DEFAULT_OPTIONS="--height ${SKIM_TMUX_HEIGHT:-40%} $SKIM_DEFAULT_OPTIONS --with-nth $n.. --bind=ctrl-r:toggle-sort $SKIM_CTRL_R_OPTS --query=${(qqq)LBUFFER} --no-multi" $(__skimcmd)) )

That simple change is enough to give me this output when I press Ctrl-r and

start typing:

Summary

I’ve been using the changes above for about 6 weeks, and I’ve found it a meaningful productivity enhancement. It turns out that I often remember enough about a command I want to recall that seeing if a match is “1d” or “7d” in the past is enough to immediately rule it in or out without scanning rightwards. Occasionally I even search on the time delta itself: if I start a match with “2d” fzf or skim will naturally search commands from 2 days ago.

But, perhaps, there is a larger point to take from this post. If, like me, you spend a lot of your life in a Unix terminal, it can be easy to fall into patterns of usage that would be recognisable to shell users from the 1970s. Not only can we do better, it’s easy to do so, and the productivity gains can be substantial!

Acknowledgements: thanks to Edd Barrett for comments.

Footnotes

One can use the fc command to find this out, but there are some

cross-platform annoyances in dealing with date formats. I used variants of

this Python code to quickly analyse my shell history:

from datetime import datetime days = {} for l in open(".zsh_history"): if len(l.split(":")) < 3: continue _, t, cmd = [x.strip() for x in l.split(":", 2)] d = datetime.fromtimestamp(int(t)).strftime("%Y-%m-%d") cmd = cmd.split(";")[1] cmds = days[d] = days.get(d, set()) cmds.add(cmd) print(len(days["2025-03-19"]))

One can use the fc command to find this out, but there are some

cross-platform annoyances in dealing with date formats. I used variants of

this Python code to quickly analyse my shell history:

from datetime import datetime days = {} for l in open(".zsh_history"): if len(l.split(":")) < 3: continue _, t, cmd = [x.strip() for x in l.split(":", 2)] d = datetime.fromtimestamp(int(t)).strftime("%Y-%m-%d") cmd = cmd.split(";")[1] cmds = days[d] = days.get(d, set()) cmds.add(cmd) print(len(days["2025-03-19"]))

Indeed, when other people have “weird” behaviour in the shell, the first thing I ask them to do is check which global environment variables have been set.

Indeed, when other people have “weird” behaviour in the shell, the first thing I ask them to do is check which global environment variables have been set.

I like fish’s out-of-the-box behaviour, but left it for two reasons. First, the differences with a POSIX shell aren’t marked improvements, but writing “normal” shell scripts then required my brain to switch modes. Second, fish defaults to making some settings like path adjustments global and permanent. I encouraged a number of people to fish: every single person (no exaggeration) ended up making the same security-worrying mistakes I did. I thus found myself no longer able to recommend it to others, at which point I wondered why I was using it myself. Such is life.

I like fish’s out-of-the-box behaviour, but left it for two reasons. First, the differences with a POSIX shell aren’t marked improvements, but writing “normal” shell scripts then required my brain to switch modes. Second, fish defaults to making some settings like path adjustments global and permanent. I encouraged a number of people to fish: every single person (no exaggeration) ended up making the same security-worrying mistakes I did. I thus found myself no longer able to recommend it to others, at which point I wondered why I was using it myself. Such is life.

I must admit that the sheer length of the Atuin installation script was the first surprise. Atuin also doesn’t currently have an OpenBSD port (i.e. “package”). That isn’t Atuin’s fault and it isn’t necessarily a show-stopper – I later made an OpenBSD port for Skim – but when I’m quickly experimenting with new software, it is a barrier.

I must admit that the sheer length of the Atuin installation script was the first surprise. Atuin also doesn’t currently have an OpenBSD port (i.e. “package”). That isn’t Atuin’s fault and it isn’t necessarily a show-stopper – I later made an OpenBSD port for Skim – but when I’m quickly experimenting with new software, it is a barrier.

The network aspects of Atuin also gave me the heebie-jeebies. Reasonable people can differ on such matters.

The network aspects of Atuin also gave me the heebie-jeebies. Reasonable people can differ on such matters.

No, I’m not sure why there’s only ' mark in there. This may

ultimately be a quirk of the awk implementation I’m using.

No, I’m not sure why there’s only ' mark in there. This may

ultimately be a quirk of the awk implementation I’m using.

I’m sure there’s a way to do this in awk, but the things I tried

didn’t seem portable across the different awk versions I tried, so I fell

back on sed.

I’m sure there’s a way to do this in awk, but the things I tried

didn’t seem portable across the different awk versions I tried, so I fell

back on sed.